Inga: a major asset for the economic development of the DRC and regional integration in Africa

Background

With the hydropower potential of Inga in Lower Congo, the DRC has a unique asset in Africa.

Well used and valued, that clean energy, which is renewable, abundant and among the least expensives in the world, will be essential for the development and the sustainable economic diversification and low carbon intensity of the DRC as well as for a significant part of the African continent. It is regarded by NEPAD and ADB as one, if not the greatest, integrative project of the Continent.

Although already identified and studied during the colonial period, the implementation of Inga project suffered, after the country’s independence in 1960, many lusts, avatars and vicissitudes.

It could be compared, during a half-century, to a real thriller, that was described brilliantly by the journalist Francois Misser in his book on the Saga Inga published by the Harmattan editions in 2013. An updating of the developments that occured since then has been made by the same author in No. 87 Situation of Congolese CREAC and published by the Royal Museum for Central Africa in 2016. With the global awareness of the dangers of global warming, the value of the potential of Inga has gained, in recent years, a new dimension that makes it today undoubtedly the most important sustainable economic resource available for DRC its future development.

The hydroelectric potential of the DRC is estimated to ± 100,000 megawatts, ± 44,000 megawatts of which concentrated on the site of Inga in Lower Congo, 225 km southwest of Kinshasa and 150 km from the mouth of the Congo River. The 56,000 MW remaining are scattered over several dozens of hydraulic sites unevenly distributed across the country. By owning 13% of global hydropower potential, the DRC ranks third in the world after Russia and China. It is remarkable that the equipment installed in the 70 and 80 on the site (Inga I and Inga II) is not important at all. It amounts 1774 MW, representing only 4% of the total potential of the site. Furthermore, because of lack of maintenance and the slow international rehabilitation programs, this ability was used, until recently, at only 40% of its capacity.

In Congo, the access to electricity in Congo is around 10%, which is, compared to an average of 35% for the continent, extremely low. In rural areas this rate hardly exceeds 1-2%.

Paradoxically, the development of Inga will only partially remedy this situation as the electricity produced will be designed for the development of large urban sites as well as for industrial and mining activities in the country and elsewhere in the Continent.

The serving in most of the territory will be economically assured only by largely decentralized production units and by other projects, involving the development of medium, small and micro hydro plants, solar, wind or using local biomass.

Unlike what happens with most of the major dams in the world, the retention basin for the final development stages of “Grand Inga high fall” will remain very small: only about fifteen Km long for an installed capacity of 39,000 MW. This is twice the Three gorges dam capacity in China. Unlike this latter, it will cause limited displacement and very few environmental damage.

Insofar as it will enable economic development less dependent on fossil fuels and reduce consumption of charcoal in large urban centers, such as Kinshasa, the project will slow further deforestation in Central Africa and have, in the end, a substantial positive ecological balance.

Key issues

If rationally and progressively implemented, the Inga site should be able to produce a large quantity of renewable clean energy, the less expensive in the world. The impact it will have on the RDC and the rest of Africa will depend heavily on strategic options and tariff policies that will be performed at the local, sub-regional, continental and sectoral levels.

These strategic tariff policies will determine the final decisive comparative advantages to have clean, abundant, renewable and very cheap energy (ex-factory cost of Kw is estimated at $ 0, 03cent). A neutral arbitration based on comparative studies between strategic interests in the medium and long term of the Congo and those of potential external partners would be necessary.

If Inga’s asset is huge, it has in fact the disadvantage of being internationally highly sought by country-level equipment suppliers as well as by potential customers; this situation has caused chronic vulnerability in Congo and brought many changes in the approaches.

During a long time, the choices have been very transparent and made difficult, because a lack of updated studies on the advantages and disadvantages of the various possible development scenarios at Continent level, particularly considering global warming and the impact on the regional integration scenarios at the continental level. Updating coherent strategic studies are still missing on the following issues :

- tariff policy dialogue at sectoral and regional levels to maximize the impact of Inga’s development in Congo, Central, Southern and Western Africa ;

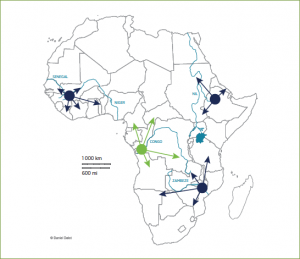

- conditions of the interconnections of the various African networks, roles and comparative advantages created by other large hydroelectric projects planned on the continent; (See Map1 annexed)

- how to ensure the mobilization of required funding and a fair distribution of risks at international level. For your information, investment costs required to complete the Grand Inga was evaluated initially at around $ 12 md for the first of seven new stages planned, namely Inga 3BC, and interconnections associated with capacity 4,800 MW. For the most part, the final cost will depend on the transmission lines that will be required in the strategic and geographical options that will be finally selected.

Among African partners who are the most interested in the development of Inga, we can find the member States of the Power Pool of Central Africa, Nigeria, Egypt and especially South Africa. The latter, heavily dependent on coal, very poluting energy, has been eyeing the enormous potential of clean, renewable energy from Inga for fifteen year.

During the first decade of the XXI century, South Africa was the spearhead of the project called WESTCOR, which created an international “offshore” company controlled by consuming countries of southern Africa and where Congo was very minor.

Unrealistic implementation conditions of Inga 3 and abandonment by BHP Billiton of its important aluminum smelter project in Moanda led to the dissolution of the Consortium.

The latest developments

On legal, technical and policy grounds very different from the Westcor project, the Inga 3 project named “INGA III low-fall” has been relaunched at the beginning of this decade, jointly by the DRC and South Africa.

This is the first of seven steps now planned to implement the “Grand Inga”. It involves the flooding of the Bundi dry valley with the construction of a large dam at its outfall.

The potential electrical power to install as part of this first phase of Grand Inga is 4,800 MW, of which 2,300 will be redeemed by the DRC to meet the growing needs of large urban centers and mining companies and 2,500 to South Africa.

A special treaty was signed between the two countries. It has just been ratified by the Congolese parliament. It recognizes the ownership and sovereignty of the DRC on the Inga site and its leadership in the process of promotion, development and implementation of the project through a National Agency for Development and Promotion of Inga (ADEPI / DRC).

The competences of this agency range from production to the sale of electricity to the construction of transport lines.

Since its creation, the new agency has been placed under the direct authority of the Presidency of the Republic of Congo. It is expected that the ADEPI enjoys a technical support provided by the World Bank;

Alongside the agency, two commissions were set up:

- a Joint Ministerial Commission;

- a Joint Permanent Technical Commission.

For further developments of the”Grand Inga” project, priority is given to the needs of the DRC while SA is given a right of first refusal on at least 20% of the new capacity that will be created at later stages.

In addition, the DRC may subsequently grant to its other external customers more favorable rates than those offered to S.A.

Following a “call for interest”, three international consortia have been shortlisted to carry out the project, including an European consortium (Spanish), a Korean consortium associated with the Canadian company SNC Lavalin and a Chinese consortium led by the company that made the Three Gorges Dam.

The final selection of the successful bidder is still to be made. In March, the head of the Agency for the development and promotion of Grand Inga announced the withdrawal of the Korean consortium. Only two groups remain in the race : one led by the Chinese companies Three Gorges and Sanhydro and the other one, the European consortium.

The beginning is planned for 2017 but this deadline could be difficult to maintain in practice.

Outlook for Belgian and European companies.

After being involved in Inga I and II issues in the 70s and 80s, Europe and especially Belgium have been marginally interested in the development of Inga for nearly 30 years.

As a consequence of problems of gas supply from Russia via Ukraine, Europe became aware of the vulnerability of its supply sources.

This led to develop an energy partnership with Africa. This partnership aims security and diversification of European supplies and integration of the energy factor in the development cooperation policies as well as the fight against global warming.

In this context, it would be logical and necessary that the energy sector and in particular the Inga issue figure prominently in the National and Regional Indicative Programmes of the EDF XI. They should be considered as key elements for the success of the regional integration and economic diversification planned in the framework of the economic Partnership Agreement Central Africa (EPAs) which includes the DRC.

If they want to run the risk of being marginalized in the context of a project of the magnitude of Grand Inga, whose achievements will take several decades and profoundly change the geography and the economic dynamics of Africa, the Belgian, Luxembourg and European companies should build alliances and join together in consortia of complementary businesses of differing sizes. I

It is a necessity to be truly competitive at European level to develop new forms of PPPs and provide varied ranges of complementary products and services such as training, standards definition and mechanisms for certification or risk spreading to better withstand competition from increasingly strong new partners like China, India, Korea and Brazil.

Aujourd’hui, avec le Luxembourg, la Belgique devrait pouvoir se profiler au niveau européen comme les champions de politiques de coopération visant à :

Belgium and Luxembourg should feel concerned in priority with the Grand Inga project and subsequent development at ports, corridors and existing economic zones.

In addition to its active role in achieving the Inga I and 2 plants, Belgium has been involved in the 70’s, through the Tractionel company (now Electrabel) in technical studies for a deep water port at Banana in the Congo estuary. This essential complement Inga II, never saw the day because of the debt crisis of the 80s that prevented funding.

Today, Luxembourg and Belgium should be able to stand for their place of champions at European level and cooperation policies to:

- to include the development of the Grand Inga and its sub-projects, which include the deep-water Port Banana and the economic corridors that must be developped to Kinshasa and then to / Brazzaville- Pointe-Noire and Luanda among the flagship projects of the Euro-African energy partnership , post COP21;

- develop new PPP adapted to the development and funding of unusual scale and long-term projects such as the present one, including a deep water port at Banana and developping economic corridors between Banana and Kinshasa or between Luanda and Pointe-Noire, passing by in Soyo and Banana;

- facilitate the participation of European companies in such projects and programs in partnership with local companies with a focus on regional integration in Africa, including Congo, its geographical position and unique asset that is Inga. It could become one of the major hubs in modern Africa. (See Box).

Conclusions

For Europe, this is an unique opportunity to become an important and active partner in one of the most promising projects for the development in the DRC, the integration of Central Africa and the future of the African continent .

It is also important to re-interest companies, universities as well as Belgian, Luxembourg and European offices of study, in a very buoyant and lengthy process whose developments will be spread over at least in the 25 next years. These projects will mobilize tens of billions of Euros, require the establishment of new public / private innovative partnerships and involve many sectors and sub-sectors. Furthermore, given the high interests that are at stakes, it is obvious that the development of Inga will have a relatively rapid international development and that it would be a pitty to miss it.